Communication between microservices - Asynchronous

Introduction to RabbitMQ and its achievements.

In an architecture focused on microservices, two of its main key concepts are: scalability and resilience. Usually, the necessity is to have a communication between microservices in some way, either to request resources or based on Event Driven. So, how we can do that without affecting directly the resilience?

This article is the first of an series that I intent to do about the forms of communication between microservices.

First of all, this approach is not a silver bullet (none is), everything will depend on the problem that your architecture will have to solve.

The fact is, the communication is complex and in these cases transparency is essential. Using the correct patterns to carry out such communication can help you to scale up and solve most of the problems that will come. Sometimes, the good and old synchronous communication via HTTP can solve your problem (even losing a “bit” in resilience).

In this article, I’ll try to show why the communication via message brokers has gained a lot of space, with names like: RabbitMQ, Kafka, ActiveMQ.

Specifically in this article I will deal with RabbitMQ, but some of these patterns are also used in other messaging technologies.

Note: if your need is to deal with microservices with the maximum resilience, check an architecture based on Event Sourcing. I wrote about autonomous microservices, you may want to read it.

What’s message brokers?

A message broker (also known as an integration broker or interface engine[1]) is an intermediary computer program module that translates a message from the formal messaging protocol of the sender to the formal messaging protocol of the receiver. — Wikipedia

A brief summary, that is a communication intermediary – Think of the logistics to send a letter, the main steps are:

- You write a letter.

- You place it in the mailbox with a specific recipient.

- Then, the post office will take care of delivering your letter.

So, as your letter will be sent and when it arrives you are no longer aware of it, you have already done your job and are “free” to carry out the other tasks.

At this way happens with message brokers, you propagate a message in a exchange (mailbox) and the message broker (post office) will send based on a logic of exchange to reach your consumer(recipient).

Why is it good?

As previously said, resilience and scalability is one of the key points of that architecture, imagine that you use communication via HTTTP, when you emit a request directly to the microservice there are some problems that you have to deal with:

- Low resilience — Send a HTTP request, in addition to latency your microservice is strong coupled to the endpoint, losing a key concept of this architecture.

- Low horizontal scaling — Usually your request will be in a internal cluster (assuming your architecture makes use of an API Gateway) and how would the load balancer of that event be done? At minimum it will be necessary to make a proxy + load balancer for each microservice or make your request go through the gateway, the big question here is: is it worth all this effort? For sure, no.

And how does it works asynchronously?

Now let’s assume the same situation above but asynchronously, and the same problems reported will be solved:

- Resilience and low coupling — Of course, both words are strong and must be sought whenever possible in any application. As your events will be sent to an intermediary (RabbitMQ) it will only be necessary to ensure that this service is working, and how the message will be sent to the recipient’s microservice will no longer be in the domain of your application… Therefore, the less you know about the recipient, more cohesive and scalable is its architecture.

- Horizontal scaling — With RabbitMQ (and any other messaging technology) a Load Balancer of your messages is automatically made, based on the form chosen by exchange by default will be Competing Workers Pattern(I will explain more about this pattern below). Anyway, the fact is, you can scale your architecture horizontally in a simple and practical way.

Asynchronous communication

The asynchronous communication is widely used when there is no need to wait for a response. However, there are cases in witch it applies, RPC is one of them.

When we wait for a response from any resource, your application is on standby waiting for a response that may never come, and to be honest it is a waste to let hardware wait for something since there is so much process that could be done, right?

Other than that, there are a few points to consider when deciding to use an asynchronous architecture:

- Low decoupling — As previously mentioned in the topics above, decoupling is great and makes the application more flexible.

- No dependency of an client library - Who has never had to create a SDK to use in internal products that required the great monolithic affectionately called API? Well, managing versions and maintaining that is a little problematic.

On this article, I’ll try to show some patterns used in message brokers step by step, and the result you can see here.

Is required that a RabbitMQ service are running, otherwise up it:

sh docker run -d -p 8080:15672 -p 5672:5672 -p 25676:25676 rabbitmq:3-management

Competing Workers Pattern

](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/4000/0*sO3z1p1s_-9Nj414.png) fonte: https://blog.cdemi.io/design-patterns-competing-consumer-pattern/

fonte: https://blog.cdemi.io/design-patterns-competing-consumer-pattern/

Competing Workers Pattern or Competing Consumers Pattern, is a pattern commonly used in a microservice architecture, as it consists of the load balancer of messages from a queue, among N consumers. That is, scaling an application that uses this pattern is very simple.

And how does this work in practice?

Alright, let’s go! First of all, we will need to create a producer.js that will be responsible for emit a event to a exchange.

When we don’t define an exchange and we emit the event directly to the queue, it will use an exchange default which will be the case here.

Let’s create an event producer, it will send a message to the named queue: messages at every second.

And in the same way we will create our consumer.js to consume the messages in the queue:

Based on the snippets above, we are “enabled” to escalate messages to N consumers.

Running both at the same time, we will have something like:

Exemplo de load balancer (competing consumers)

Exemplo de load balancer (competing consumers)

Realize that the messages are divided among consumers.

The sample code has here. If you want to know more about this pattern, this is a good start.

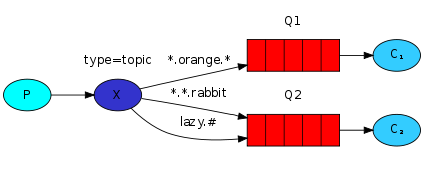

Topics Pattern

Sending events directly to a queue is simple and easy, however when the architecture grows, new patterns are needed.

Imagine that it is necessary to broadcast an event for more than one queue - “Oh, just put the name of the queue and send!” - Unfortunately that is not how it works. Defining queues and sending ends up leaving your application attached! Ideal would be to send only to a “queue” and it would try to forward a certain event to its respective queue/consumer, right? There are Topics Pattern for that!

Breaking logs by levels can increase the flexibility of your application.

Events sent for a topic must contain an argument called routing_key which must be a list of words separated by a dot (.). Example: log.warning or log.critical. Therefore, an event sent to topic exchange will be delivered to all queues in which to “match” with the routing_key passed.

Imagine that we have 3 queues:

- warning.logs — To deal with some business rule on warnings.

- critical.logs — To deal with some business rule on critical errors.

-

logs - Responsible for saving any type of log, so your bind will be

log.*. The asterisk () indicates that it can be replaced by *any word.

There is also #, which can be replaced by zero or more words

Here is an example of two consumers(right corner) and one producer(left corner), where consumer1.js (top right) will only wait for #.critical.# events and consumer2.js(bottom right) will wait for all events.

The example code is here

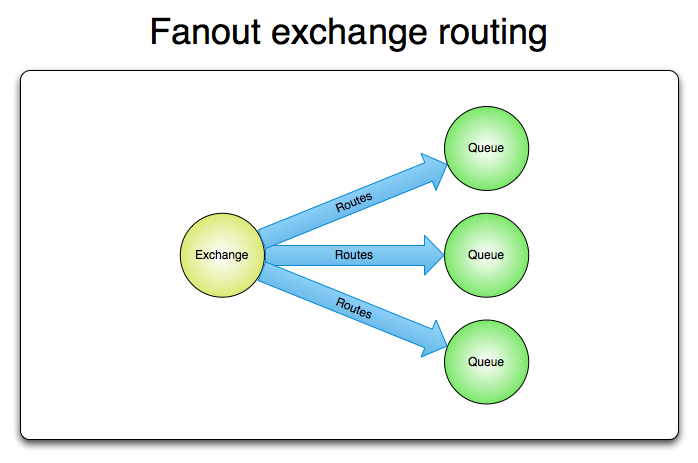

Fanout Pattern

Topics gave us a lot of flexibility. However, as shown, he continues to follow the Pattern Competing Workers. What if we wanted to broadcast this event to several queues?

This Pattern is widely used not only with message brokers but in microservices architecture in general, it’s worth checking out!

When propagating a message to a fanout exchange we have the flexibility to escalate a message without having to specifically create a queue for it. This allows us to launch an event in which it will be processed by all consumers who are listening to queue or exchange.

For instance, a e-commerce, when finalizing a sale we need to do two different tasks:

-

Perform the sale to financial

-

Send to payment service

And here is an example of the application running, its source code you can check out here.

RPC Pattern

](https://cdn-images-1.medium.com/max/2000/1*vkYkMgb7KYl3qZiAVX9SOA.png) source: http://alvaro-videla.com/2010/10/rpc-over-rabbitmq.html

source: http://alvaro-videla.com/2010/10/rpc-over-rabbitmq.html

When sending an asynchronous message, most of time we send actions and not questions. However, there are scenarios where it will be necessary to request some resources and wait for an answer; for this, there is a well-known pattern called Remote Procedure Call or just RPC.

Let’s imagine a scenario where it will be necessary to request a user for an RPC microservice based on their ID.

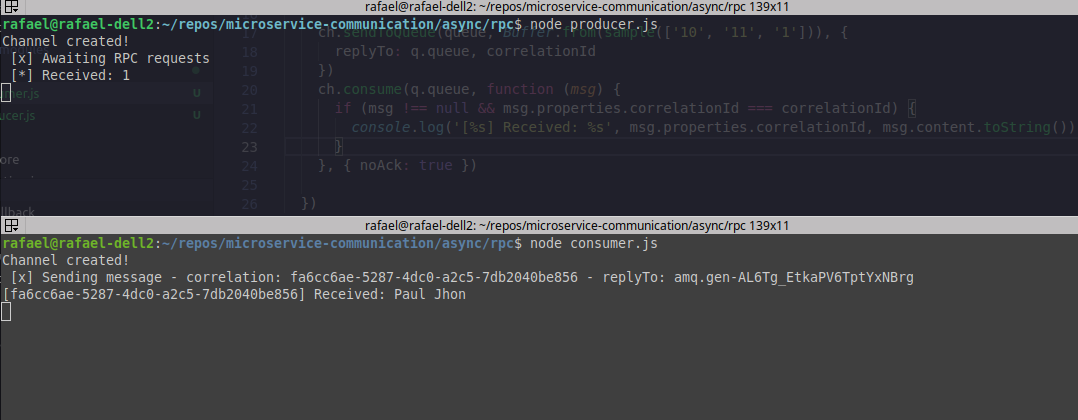

Based on the image above:

-

Producer — User service, which will be waiting for RPC requests to answer them.

-

Consumer — Service which user has a dependency, will send the requested user ID to receive the user’s name.

See that the producer received an ID: “[] Received: 1” and thus, the consumer received the name of the requested user: “[uuid] Received: Paul Jhon” therefore the process of request/reply* worked perfectly.

Well… I imagine some doubts have arisen:

- What’s the UUID?

- What’s the replyTo?

When sending a question asynchronous we also received a asynchronous answer** and how do I know the correlation between question number 1 and answer number 1?

In asynchronous communication you will hardly be able to guarantee that messages arrive in their natural order (1, 2, 3 … 99).

This is where correlation_id is used, it will be the link between question number 1 and answer number X.

Now, going back to the example image above, we send a message with UUID/correlation_id fa6cc6a2-XXXXX-856 and we receive the answer containing the same correlation_id, therefore, we guarantee that this answer will refer to the above question.

And the replyTo?

Well, it is the name of the queue to which the response will be sent. A microservice that waits for RPC requests should not have a response queue, as the questions may come from many other services. Therefore, upon receiving the replyTo parameter, it will know which queue to respond to. A simple queue callback.

You can find the code for this example here.

Final consideration

In this article, I tried to approach the communication between microservices with RabbitMQ in the most theoretical way possible, but if I miss lines of code, I created a repository with all the code examples that I will use in this series.

Note: the documentation of RabbitMQ is excellent and very simple! It’s worth to check it.

Social networks: Github, Twitter